Part I: The Dawn of an Idea (1800s – Early 1900s)

Beyond Transportation – The Birth of the Pleasure Voyage

While sea travel in the early 1800s was dominated by sailing packets and nascent steamships focused on mail, cargo, and the vast emigrant trade, the first seeds of leisure cruising were sown in the Mediterranean.1 Some historians point to the

Francesco I, flying the flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, as the first true cruise ship.5 In June 1833, preceded by a formal advertising campaign, this vessel departed Naples carrying European nobles, authorities, and royal princes on a curated three-month journey. With planned excursions to cultural epicenters like Athens, Smyrna, and Constantinople, its purpose was unequivocally pleasure, setting a precedent for sea travel as a luxurious, curated experience for the elite.5

However, it was a British company that commercialized this aristocratic ideal and made it accessible to a paying public. The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) was established in 1837 by Brodie McGhie Willcox, Arthur Anderson, and Captain Richard Bourne to operate a mail and passenger service between England and the Iberian Peninsula.7 In 1844, in a move that would define the future of an industry, P&O began advertising the first commercial “sea tours.” For a ticketed price, tourists could embark from Southampton on a voyage to Mediterranean destinations such as Gibraltar, Malta, and Athens.6 These were the forerunners of modern cruise holidays, marking the birth of cruising as a repeatable, commercial product.1

The concept soon crossed the Atlantic. In 1867, the wooden paddle steamer Quaker City embarked on the first pleasure cruise to depart from North America.10 Aboard was the prominent American author Mark Twain, whose subsequent travelogue,

The Innocents Abroad, provided a witty and invaluable account of the experience. His writing captured the contrast between the romantic allure of the “Grand Tour” and the often-uncomfortable realities of early sea voyages, immortalizing the journey for a global audience.10

A Tale of Two Decks – The Early Passenger Experience

The passenger experience aboard these 19th-century vessels was a world of stark contrasts, a microcosm of the era’s rigid class structure. While the notion of leisure cruising was taking root in first class, the financial engine of the shipping industry was the mass transport of emigrants in unimaginably grim conditions.

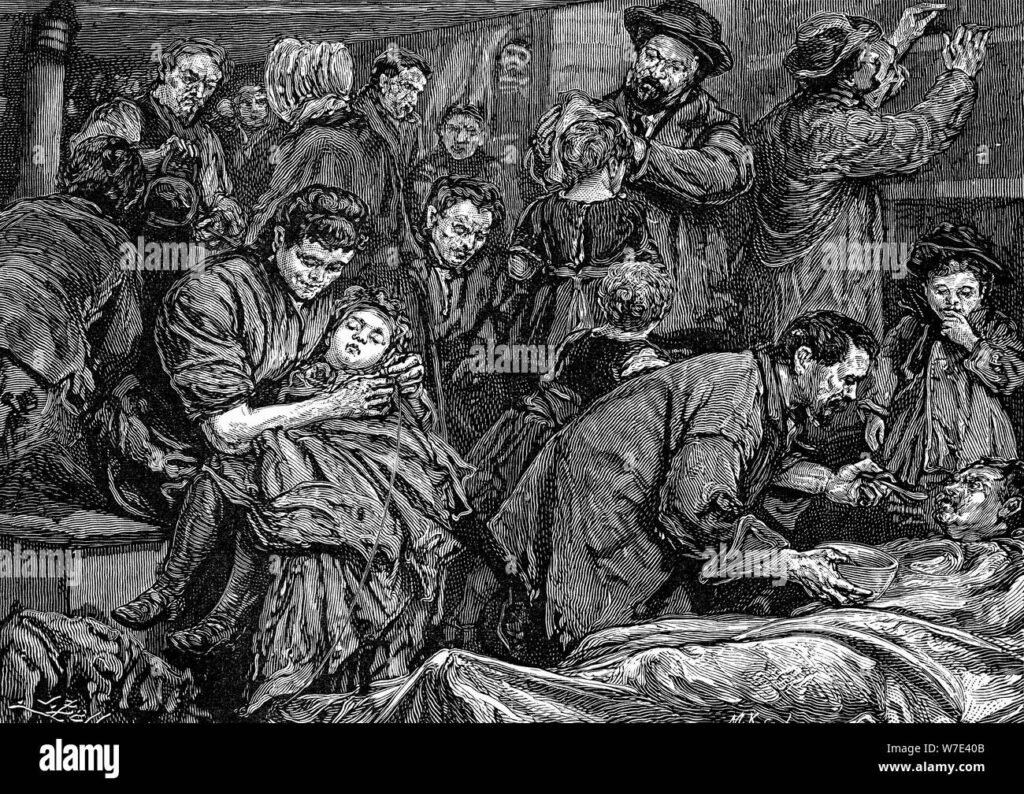

The term “steerage” originally referred to the part of a ship’s lower deck where the steering equipment was housed.16 It came to mean the lowest class of travel, in converted cargo holds that were dark, cramped, and poorly ventilated.16 For millions fleeing famine and political upheaval in Europe, this was the only way to cross.16 Passengers were treated as human cargo, crammed into mixed-gender berths with little privacy.16 On the earliest Atlantic steamships, they were even berthed alongside the ship’s livestock—cows and chickens kept to provide fresh milk, eggs, and meat for the first-class passengers above.16 Emigrants were typically required to bring their own food and bedding for voyages that could last several weeks.16 Confined below decks during storms without access to fresh air or proper sanitation, disease was rampant.16 As one diary from the period noted, “Between decks was like a loathsome dungeon”.19

Steerage passengers on the deck of an Atlantic steamer, circa 1850. For millions of emigrants, the journey to the New World was endured in crowded, unsanitary conditions, a stark contrast to the emerging comforts of first-class travel.

Meanwhile, on the upper decks, a different world was emerging. Visionary shipping magnates like Samuel Cunard, who founded his line in 1840 to secure a transatlantic mail contract, quickly recognized the importance of passenger comfort.22 An early anecdote from Cunard’s first ship, the RMS

Britannia (1840), tells of a cow being kept on board to supply fresh milk to passengers on the 14-day crossing—a simple but significant gesture of service.13 By the 1850s and 1860s, shipping lines began to cater more exclusively to passengers, adding luxuries that were revolutionary for the time, such as electric lights, dedicated deck space for strolling, and organized entertainment.13 The revenue generated from the masses in steerage ironically funded the development of these amenities, creating a financially codependent yet socially segregated world within the confines of a single hull.

The First of Her Kind – Prinzessin Victoria Luise

The true birth of the purpose-built cruise ship can be credited to the vision of one man: Albert Ballin, the director of Germany’s Hamburg-America Line (HAPAG).4 His initial idea was a pragmatic business solution to an operational problem. His grand transatlantic liners were forced to sit idle during the harsh winter months when the North Atlantic was too treacherous for regular crossings.5 To generate revenue during this downtime, Ballin decided to send his ships on long southern cruises to warmer climates.6 He first tested this concept in 1891 with the liner

Augusta Victoria, sending her on a cruise to the Mediterranean and the Near East with 241 passengers.5

The voyage was a success, but Ballin realized that a repurposed ocean liner, designed for the rigors of the North Atlantic, was not ideal for leisure cruising. It was too large to enter smaller, scenic ports, and its accommodations were too austere for wealthy travelers seeking a true luxury experience.26 This led him to a revolutionary conclusion: a new type of ship was needed, one built not for transport, but exclusively for pleasure.

In 1899, Ballin commissioned the shipbuilder Blohm & Voss to construct this vessel.26 Launched on June 29, 1900, the SS

Prinzessin Victoria Luise was the world’s first purpose-built cruise ship.2 She was intentionally designed to look like an elegant private yacht, with a sleek white hull and a clipper bow, to appeal to a wealthy clientele who aspired to that lifestyle but could not afford the upkeep of their own vessel.5 At 407 feet long and 4,419 tons, she was a marvel of her time, capable of a respectable 16 knots.26

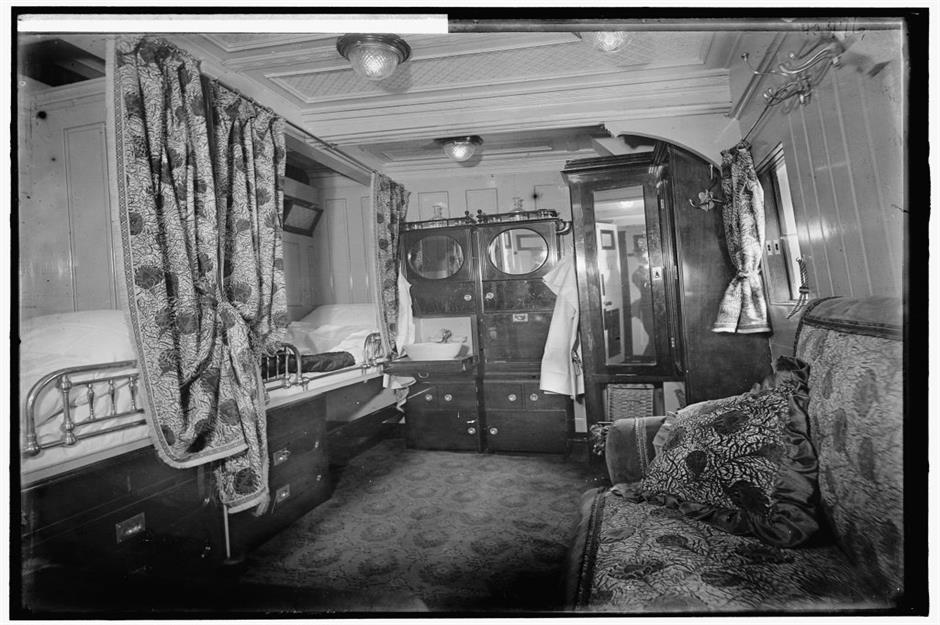

Her onboard amenities set a new standard for luxury at sea and became the blueprint for all future cruise ships. The Victoria Luise contained 120 opulent, first-class-only cabins, a well-equipped gymnasium, a library, a grand ballroom for social gatherings, and even a darkroom for the development of film by amateur photographers.5 The ship introduced the concept of the “floating hotel,” where the service and style were intended to rival the finest establishments in Europe.5 She embarked on her first 35-day cruise to the West Indies and Venezuela, later sailing to the Mediterranean and the Baltic.26 Tragically, her career was cut short in December 1906 when she ran aground on an uncharted reef off the coast of Jamaica and was declared a total loss, though all passengers were rescued safely.10 Despite her short life, the

Prinzessin Victoria Luise proved the viability of purpose-built luxury cruising and forever changed the course of maritime travel.

A first-class stateroom aboard the SS Prinzessin Victoria Luise (1900). As the world’s first purpose-built cruise ship, her 120 cabins were designed to emulate the finest European hotels, setting a new standard for luxury at sea.

Part II: The Golden Age of the Ocean Liner (1900s – 1950s)

The early 20th century marked the zenith of the ocean liner. These magnificent vessels were more than just a means of transport; they were floating showcases of national power, technological innovation, and artistic expression.27 The North Atlantic became a competitive arena where the great shipping lines of Great Britain, Germany, and France vied for supremacy, building ships that were progressively larger, faster, and more luxurious.4 This era, often called the “Golden Age,” produced some of the most legendary ships in history, vessels that captured the public imagination and defined an era of elegance and ambition.

The Battle for the Atlantic – National Pride and the Blue Riband

The rivalry between nations was most fiercely embodied in the quest for the Blue Riband, an unofficial but highly coveted honor awarded to the passenger liner with the fastest average speed on a westbound transatlantic crossing.4 For much of the 19th century, British lines, particularly Cunard, had dominated this contest.25 However, at the turn of the 20th century, the newly unified German Empire mounted a serious challenge. Ships like Norddeutscher Lloyd’s

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse (1897) and HAPAG’s Deutschland (1900) snatched the Blue Riband, stunning the British maritime establishment and turning the competition into a matter of national pride.4

This German ascendancy prompted a direct response from the British government, which, concerned about its naval prestige, provided Cunard Line with substantial loans and an annual subsidy to build two “superliners” capable of reclaiming the record.23 This government intervention elevated the ships from purely commercial enterprises to “Ships of State,” symbols of national might and technological prowess.27 The competition spurred a technological arms race that saw rapid advancements in naval architecture and engineering. Hulls transitioned from iron to stronger, lighter steel, as seen in P&O’s

SS Ravenna in 1880.6 Inefficient paddle wheels gave way to powerful screw propellers.3 The most significant innovation, however, was the adoption of the revolutionary steam turbine engine, first pioneered on a large scale in Cunard’s new record-breakers. This technology provided immense power, allowing for greater speeds and a smoother, less vibration-prone voyage for passengers.22

Floating Palaces – A Study in Opulence

The great liners of the Golden Age were conceived as “floating palaces,” with interiors designed to rival the most opulent hotels and country manors on land.22 The prevailing design philosophy was one of terrestrial replication; the goal was to make passengers forget they were on a ship at all, surrounding them with familiar grandeur.19 This era produced a series of iconic vessels, each with a distinct character.

Case Study 1: RMS Mauretania (1906)

The RMS Mauretania and her sister ship, Lusitania, were Cunard’s government-backed response to the German challenge.22 Powered by massive steam turbines, the

Mauretania was an engineering marvel built for one primary purpose: speed. She captured the Blue Riband on her return maiden voyage in 1907 and held it for an astonishing 22 years, a record that remains unbeaten.10 Her interiors were a showcase of Edwardian elegance, designed by Harold Peto. The first-class public rooms featured extensive use of rich mahogany, walnut, and oak paneling, adorned with intricate carvings and lavish fabrics, creating an atmosphere of a distinguished English country house at sea.35 She was the epitome of speed combined with stately comfort.

The opulent First Class Lounge of the RMS Mauretania (1906). A masterpiece of Edwardian design, the lounge showcased the luxurious appointments that, combined with her record-breaking speed, made her the queen of the Atlantic for two decades.

Case Study 2: RMS Titanic (1912)

While Cunard focused on speed, its main rival, the White Star Line, competed on size and luxury.4 The company’s

Olympic-class ships—Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic—were designed to be the largest and most luxurious vessels afloat. The RMS Titanic offered amenities that were unprecedented for their time, including an indoor swimming pool, a Turkish bath complex, a squash court, and a fully equipped gymnasium.13 Her interiors were a pastiche of historical styles, meticulously researched to evoke the grandeur of European stately homes. The first-class dining saloon was decorated in a Jacobean style inspired by houses like Hatfield House, while the lounge was modeled after the Palace of Versailles.33 The ship was a floating microcosm of the rigid Edwardian social hierarchy. First-class passengers resided in lavish suites, some with private promenades, and had exclusive access to the ship’s finest amenities. Second class offered comfort comparable to first class on other lines, while third class, though a significant improvement over the steerage of the 19th century with enclosed cabins and a dedicated dining room, remained distinctly separate and spartan.29

IThe Grand Staircase of RMS Olympic, identical to that of her ill-fated sister, RMS Titanic. This magnificent structure, crowned with a glass dome, was the heart of the ship’s first-class section and a symbol of the era’s unparalleled maritime luxury.

Case Study 3: SS Normandie (1935)

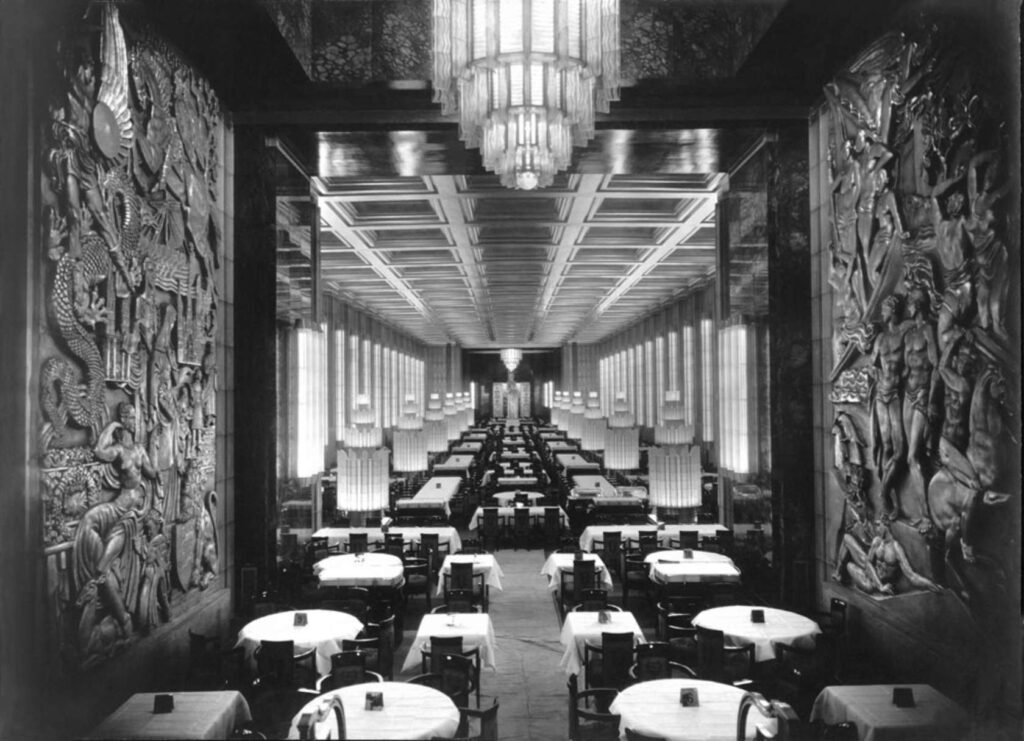

Often called the most beautiful ocean liner ever built, the French Line’s SS Normandie was a triumph of art and engineering.10 Launched in 1932, she was a floating masterpiece of the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne styles that defined the interwar period.41 Her interiors were a showcase for France’s finest artists and designers, including René Lalique, Jean Dupas, and Raymond Subes.41 The centerpiece was the breathtaking three-deck-high first-class dining room. At 305 feet, it was longer than the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and was illuminated not by traditional chandeliers, but by 12 towering pillars of Lalique glass, earning the

Normandie the nickname “The Ship of Light”.45

Her technical innovations were as revolutionary as her design. The hull, designed by Russian naval architect Vladimir Yourkevich, featured a radical clipper-like bow with a bulbous forefoot below the waterline, a combination that made her incredibly hydrodynamic and efficient.47 She was also one of the first liners to be equipped with a primitive form of radar.47 Instead of a direct-drive steam turbine system, she used a turbo-electric propulsion plant, where turbines generated electricity to power enormous motors that turned the propellers. This system was exceptionally smooth and quiet, adding to the ship’s luxurious feel.48 The

Normandie was the ultimate expression of the liner as a work of art and a symbol of national genius.

The breathtaking First-Class Dining Room of the SS Normandie (1935). An icon of Art Deco design, the hall was longer than the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and illuminated by 12 pillars of Lalique glass, earning the ship the nickname “The Ship of Light.”

From Grand Saloons to Troop Decks – The Liners at War

The glamour of the Golden Age was twice interrupted by global conflict, during which these luxurious liners were called into national service. In both World War I and World War II, the great ships were requisitioned by their respective governments and converted into troop transports or hospital ships.2 Their luxurious fittings were carefully removed and placed in storage, their elegant hulls were painted in drab grey or dazzling camouflage, and their grand public rooms were filled with thousands of bunks.31 Their immense size and, crucially, their speed made them invaluable assets for moving vast numbers of soldiers across hostile oceans.51 Cunard’s

Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth were particularly effective during World War II, capable of carrying up to 15,000 troops on a single voyage at speeds that allowed them to outrun German U-boats. Their contribution was so significant that Winston Churchill credited them with having shortened the war by at least a year.22

In a darker chapter of this period, the Nazi Party in Germany co-opted the idea of leisure cruising for its own ends. Through the “Kraft durch Freude” (Strength through Joy) program in the 1930s, the regime operated cruise ships like the Wilhelm Gustloff and Robert Ley to provide affordable holidays for German workers.10 While presented as an act of benevolence, these voyages served as a powerful propaganda tool, showcasing the supposed benefits of the National Socialist state while providing a captive audience for indoctrination.10

Part III: The Great Pivot – Cruising in the Jet Age (1950s – 1980s)

The post-war era saw a brief resurgence of the ocean liner’s glamour, but a new technology was on the horizon that would render these magnificent ships obsolete almost overnight. The advent of the commercial jetliner in the late 1950s triggered an existential crisis for the passenger shipping industry, forcing a radical reinvention. This period of disruption and adaptation marked the end of the ocean liner as the primary means of intercontinental travel and the true beginning of the modern cruise industry.

The End of the Line – The Rise of Air Travel

For over a century, the great liners had been the only way to cross the ocean. By the mid-1950s, however, transatlantic air travel was becoming faster, more convenient, and increasingly affordable.2 The launch of regular jet services across the Atlantic in 1958 was the death knell for the liner trade.4 A journey that took five days by sea could now be completed in a matter of hours.1 The passenger shipping lines, once the titans of global transport, saw their primary business model evaporate.5

The grand ocean liners of the Golden Age were fundamentally ill-suited for the emerging leisure cruise market. Their design reflected their purpose: fast, all-weather transport across the harsh North Atlantic. This resulted in several critical disadvantages for cruising 5:

- High Fuel Consumption: Their powerful engines, built for speed, were incredibly thirsty, making slower-paced leisure voyages uneconomical.6

- Deep Draft: Their deep hulls, necessary for stability in the open ocean, prevented them from entering the smaller, more picturesque ports that were desirable on a cruise itinerary.6

- Passenger Accommodations: Their cabins were designed to maximize capacity for point-to-point transport, resulting in a high number of small, windowless interior rooms that were undesirable for a vacation experience.5

- Lack of Amenities: They often lacked features that would become standard on cruise ships, such as ample open deck space and outdoor swimming pools.53

Reinventing the Voyage – From Transport to Floating Resort

Faced with fleets of unprofitable ships, the surviving companies had to pivot to survive. The answer was to reinvent the voyage itself. Instead of selling transportation from Point A to Point B, they began marketing the ship as a destination in its own right—a floating resort.1 The focus shifted to shorter, round-trip “pleasure tours” from major hubs like New York and Miami to warm-weather destinations in the Caribbean and Bermuda.1

This shift required a fundamental change in the passenger experience. The rigid formality and class distinctions of the liner era began to dissolve. Dress codes were relaxed, and onboard life became more casual.1 Entertainment, once a secondary diversion, became a primary attraction. Shuffleboard and deck quoits were supplemented by cabaret shows, live bands, and themed party nights, all designed to appeal to a broader, middle-class audience of holidaymakers.1

Some shipping lines attempted to bridge the gap between the old and new worlds by building “dual-purpose” liners. These ships were designed to serve the traditional transatlantic route during the peak summer season but could be easily adapted for one-class cruising in the winter.6 The most famous and successful of these was Cunard’s

Queen Elizabeth 2 (QE2), launched in 1969. With an ingenious system of sliding panels and flexible public rooms, she could seamlessly transition between a two-class liner and a one-class cruise ship, allowing her to remain viable long after her contemporaries were scrapped.6

The New Wave – The Founding of Modern Cruising

While the old, established lines struggled to adapt their legacy fleets and mindsets, a new wave of entrepreneurs saw an opportunity. In the 1960s and 1970s, a series of new companies were founded with the sole purpose of leisure cruising. Unburdened by the history and operational costs of the liner trade, they built ships specifically for the burgeoning Caribbean market, laying the foundation for the modern cruise industry.10

These pioneers included:

- Princess Cruises, founded in 1965 by Stanley B. McDonald, who began by chartering a small vessel for cruises to the Mexican Riviera.10

- Norwegian Cruise Line, founded in 1966.10

- Royal Caribbean Cruise Line, established in 1968 by a consortium of Norwegian shipping companies specifically to build ships for year-round Caribbean cruising from Miami.10

- Carnival Cruise Lines, founded in 1972 by Ted Arison with a revolutionary vision to democratize cruising and market it as a fun, affordable vacation for the masses.10

The ascent of this new industry was dramatically accelerated by a cultural phenomenon. In 1977, the television show The Love Boat premiered, set aboard the ships of Princess Cruises. The series, which ran for a decade, portrayed cruising as a romantic, glamorous, and accessible getaway filled with adventure and fun.1 It became a weekly advertisement beamed into millions of American homes, demystifying the cruise experience and cementing it in the popular imagination as the ultimate vacation. The impact was immense, fueling a surge in demand that propelled the industry into an era of explosive growth.2

Part IV: The Age of the Mega-Ship (1980s – Present)

The foundation laid in the 1960s and 70s gave way to an era of unprecedented expansion from the 1980s onward. Fueled by the mainstream popularity of cruising, a fierce competition erupted among the major lines. This new “battle for the Atlantic”—now fought primarily in the Caribbean—was not over speed, but over size and spectacle. The result was the “Cruise Boom,” a period of rapid shipbuilding that saw the birth of the “mega-ship” and the transformation of the cruise vessel from a floating resort into a veritable floating city.2

Bigger is Better – The “Cruise Boom” and the First Mega-Ship

The mantra of the 1980s cruise industry was simple: bigger is better. Larger ships offered economies of scale and, more importantly, the space to add more restaurants, pools, and show-stopping attractions that could be used as powerful marketing tools.2 This competitive drive culminated in 1988 with the launch of a vessel that would forever change the scale of cruising: Royal Caribbean’s

Sovereign of the Seas.5

Widely regarded as the industry’s first “mega-ship,” the Sovereign of the Seas was a quantum leap in size and design. At 73,192 gross tons, she was the largest passenger ship built since the Queen Elizabeth five decades earlier and nearly twice the size of her contemporaries.55 Her most revolutionary feature was a spectacular, multi-story atrium with glass elevators and a grand piano at its base.55 This design choice shifted the architectural focus of the ship inward, creating an immediate “wow factor” the moment a passenger stepped aboard and setting a design standard that would be emulated for decades. Furthermore,

Sovereign pioneered the concept of dedicating an entire deck to cabins with private balconies, transforming what was once a rare luxury into an attainable feature that fundamentally altered passenger expectations and ship design.5

The Floating City – The Oasis Class and Beyond

The launch of Sovereign of the Seas initiated an arms race for size and innovation that continued for the next two decades. This evolution reached its apogee in 2009 with the debut of another Royal Caribbean vessel, Oasis of the Seas. At 225,282 gross tons, she was nearly three times the size of Sovereign and so large that the term “mega-ship” no longer seemed adequate. She was, in effect, a floating city.

The key innovation of the Oasis Class was its revolutionary design, which split the superstructure down the middle to create a series of distinct, themed “neighborhoods”.61 These included:

- Central Park: An open-air park in the heart of the ship, featuring thousands of live trees and plants, winding pathways, and al fresco dining.62

- Boardwalk: A nostalgic, family-friendly area reminiscent of a seaside pier, complete with a full-sized, hand-carved carousel and the stunning outdoor AquaTheater for high-diving and acrobatic shows.62

- Royal Promenade: An indoor “main street” lined with shops, pubs, and cafes, serving as the ship’s social hub.61

This neighborhood concept was a brilliant solution to the challenge of scale. It broke down the immense vessel into more intimate, manageable zones, improved passenger flow, and allowed for an unprecedented variety of experiences on a single ship.62 The design cemented a fundamental shift in the cruise value proposition: the ship was no longer just a means to visit destinations; it

was the destination. The class evolved with subsequent ships, each adding new features: Harmony of the Seas (2016) introduced the ten-story Ultimate Abyss dry slide, and Wonder of the Seas (2022) added an eighth, exclusive Suite Neighborhood.62

The Pinnacle of Modern Cruising – A Profile of Icon of the Seas

The relentless push for innovation has culminated in the current pinnacle of cruise ship design, Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas. Launched in January 2024, she is the first of the new Icon Class and the largest cruise ship in the world.65 Her statistics are staggering: a gross tonnage of 250,800, a length of 1,198 feet, and a maximum capacity for 7,600 passengers and 2,350 crew.66 A significant technological leap is her propulsion system. She is the line’s first ship to be powered by six dual-fuel engines that run on Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), a much cleaner-burning fuel that significantly reduces emissions.66

The onboard experience is designed around eight neighborhoods, five of which are new concepts that push the boundaries of entertainment at sea 66:

- Thrill Island: Home to “Category 6,” the largest waterpark at sea, featuring six record-breaking waterslides, including the first open free-fall slide on a cruise ship.66

- AquaDome: A massive, shimmering geodesic dome perched at the front of the ship. By day, it’s a tranquil lounge with panoramic ocean views; by night, it transforms into an entertainment venue featuring a 55-foot waterfall and dazzling aquatic performances.66

- Surfside: The first neighborhood dedicated entirely to young families, with splash pads, a carousel, an arcade, and family-friendly dining options.66

- The Hideaway: A multi-level, adults-only beach club with the first suspended infinity pool at sea, located 135 feet above the ocean.66

Icon of the Seas represents the full realization of the ship as a self-contained vacation destination, a floating metropolis engineered to compete not with other ships, but with the world’s leading land-based resorts and theme parks.

Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas during sea trials in 2023. As the world’s largest cruise ship and the first in its class to be powered by LNG, she represents the current pinnacle of maritime engineering and the “floating city” concept.

The Carnival “Fun Ship” Philosophy

While Royal Caribbean pushed the boundaries of size and hardware, another industry giant carved out its dominance with a different, but equally revolutionary, strategy. Carnival Cruise Line, founded by Ted Arison in 1972, fundamentally democratized cruising.58 Arison’s vision was to strip away the perceived elitism of sea travel and rebrand it as a fun, high-energy, and affordable vacation for the average person—the “Fun Ship” concept.59

The company’s beginnings were humble and somewhat infamous. Its first vessel was a second-hand transatlantic liner, the former Empress of Canada, renamed TSS Mardi Gras.57 On her maiden voyage from Miami, she famously ran aground on a sandbar, an embarrassing incident that, thanks to widespread media coverage, ironically provided the fledgling company with invaluable name recognition.59

From these rocky beginnings, Carnival grew rapidly by catering to a market segment its competitors had largely ignored. The onboard atmosphere was deliberately less formal and more boisterous, with a focus on casinos, nightclubs, and lively entertainment. The ship interiors, many designed by Joe Farcus, were known for their vibrant, often flamboyant, themes that prioritized fun over subdued elegance.57 After launching its first purpose-built ship, the

Tropicale, in 1982—which introduced the line’s now-iconic red, white, and blue winged funnel—Carnival embarked on an aggressive shipbuilding program.57 This included the eight-ship Fantasy class and, in 1996, the

Carnival Destiny. At 101,000 gross tons, she shattered a psychological barrier, becoming the world’s first passenger ship to exceed 100,000 tons and briefly holding the title of the world’s largest.57 Carnival’s focus on accessibility and fun played a crucial role in expanding the cruise market far beyond its traditional wealthy demographic.

| The Growth of the Mega-Ship | |||||

| Ship Name | Cruise Line | Year Launched | Gross Tonnage | Max Passenger Capacity | Key Innovation |

| Sovereign of the Seas | Royal Caribbean | 1988 | 73,192 | 2,744 | First “mega-ship”; introduced the multi-story atrium. |

| Carnival Destiny | Carnival Cruise Line | 1996 | 101,353 | 3,392 | First passenger ship to exceed 100,000 gross tons. |

| Voyager of the Seas | Royal Caribbean | 1999 | 138,194 | 3,840 | Introduced resort-like features: ice rink, rock wall, Royal Promenade. |

| Queen Mary 2 | Cunard Line | 2004 | 148,528 | 3,090 | The only true modern ocean liner, built for transatlantic crossings. |

| Oasis of the Seas | Royal Caribbean | 2009 | 225,282 | 6,296 | Introduced the revolutionary “neighborhood” concept. |

| Wonder of the Seas | Royal Caribbean | 2022 | 235,600 | 7,084 | World’s largest ship (at launch); introduced the Suite Neighborhood. |

| Icon of the Seas | Royal Caribbean | 2024 | 250,800 | 7,600 | World’s largest ship; LNG-powered; features largest waterpark at sea. |

Part V: The Enduring Culture of the Sea

Despite their transformation into floating technological marvels, modern cruise ships remain deeply connected to a maritime culture stretching back centuries. This connection is visible in the enduring traditions, superstitions, and the unique logistical realities of operating a self-contained city at sea. These cultural threads provide a fascinating link between the age of sail and the age of the mega-ship, revealing that the human element of seafaring remains a powerful constant.

Traditions and Superstitions

The life of a cruise ship is steeped in ceremony and ritual, much of it inherited from naval tradition and ancient sailor’s lore. The creation of a new vessel is not merely a construction project; it is a series of milestone events, each with its own significance.70

- Steel Cutting: The process begins with the formal cutting of the first piece of steel, a ceremony attended by cruise line and shipyard executives to mark the official start of the build.70

- Keel Laying and the Coin Ceremony: A major milestone is the laying of the keel, the ship’s structural backbone. This event is often marked by the coin ceremony, an ancient tradition where newly minted coins are welded into the keel block. This practice is believed to bring good luck to the ship and all who sail on her.70

- Float Out: This is the first time the ship touches water. The dry dock is flooded, and the vessel floats for the first time. This is often accompanied by a blessing from a chaplain.70

- Sea Trials: Before delivery, the ship is taken out to sea for a series of rigorous tests to assess its speed, maneuverability, safety systems, and noise levels.70

- Christening and the Godmother: The most public of these traditions is the christening ceremony. Every new ship is officially named by a godmother, a prominent figure who bestows her blessing upon the vessel. The ceremony culminates in the godmother triggering the release of a bottle of champagne to smash against the hull—a ritual believed to ensure good fortune.70 Should the bottle fail to break, it is considered a very bad omen.70 Over the years, godmothers have included royalty, such as Queen Elizabeth II, and cultural icons like Oprah Winfrey and Malala Yousafzai.71

Even the architecture of the ship is influenced by superstition. Many Western cruise lines will omit a Deck 13, jumping straight from 12 to 14 in elevators and on deck plans, to avoid tempting fate with the unlucky number.72 In a fascinating cultural variation, Italian-founded lines like MSC Cruises have a Deck 13 but will often omit Deck 17. This is because the Roman numeral for 17, XVII, is an anagram of the Latin word VIXI, which translates to “I have lived”—a phrase with ominous, funereal connotations implying one’s life is over.72

A Look Inside – Fascinating Facts and Logistics

Operating a modern mega-ship is akin to managing a small, mobile city, requiring incredible logistical coordination and self-sufficiency. Behind the passenger-facing glamour lies a complex world of engineering, supply chain management, and community services.

Logistical Marvels:

- Power and Water: A large cruise ship’s diesel-electric power plant can generate over 80 megawatts of electricity, enough to power a town of 80,000 homes.75 They are also entirely self-sufficient in water, producing up to 250,000 gallons of fresh water each day from seawater using advanced reverse osmosis and evaporation systems.75

- Food Consumption: The scale of catering is immense. On a typical seven-day voyage, a large ship carrying 6,000 passengers will consume approximately 200,000 pounds of food, including roughly 60,000 eggs, 15,000 pounds of beef, 9,000 pounds of lettuce, and 700 gallons of ice cream.72

- Waste Management: These floating cities are equipped with sophisticated waste management facilities that can process tons of waste daily. They employ extensive recycling programs, food biodigesters that turn organic waste into liquid, and high-temperature incinerators to minimize their environmental footprint.66

The Hidden City:

Beyond the public areas, every cruise ship contains a hidden city with facilities to handle any eventuality and cater to the needs of its diverse population.

- Morgue and Brig: It is a little-known but practical fact that all cruise ships are equipped with a small morgue to hold the body of any person who passes away at sea until the next major port. They also have a brig, or jail, a secure room used to detain any passenger who poses a threat to themselves or others until they can be handed over to local authorities.71

- Secret Codes: To maintain discretion, cruise lines use coded announcements in their daily programs for passenger meet-ups. A call for “Friends of Bill W.” is a meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous, while “Friends of Dorothy” is a gathering for LGBTQ+ passengers and allies.72

- Crew Life: The thousands of crew members, who can represent over 60 different nationalities, live in a world entirely separate from the guests.75 On the lower decks, they have their own cabins, mess halls, bars, gyms, and recreational areas, forming a unique and vibrant multicultural community that keeps the city afloat and running 24 hours a day.71

From the ancient coin welded to the keel of the world’s most advanced ship to the quiet operation of its onboard morgue, the cruise ship remains a fascinating intersection of modern engineering and enduring human culture. It is a world that has evolved from a simple mail packet into a floating metropolis, yet it still sails with the traditions and practicalities of the sea in its very bones.