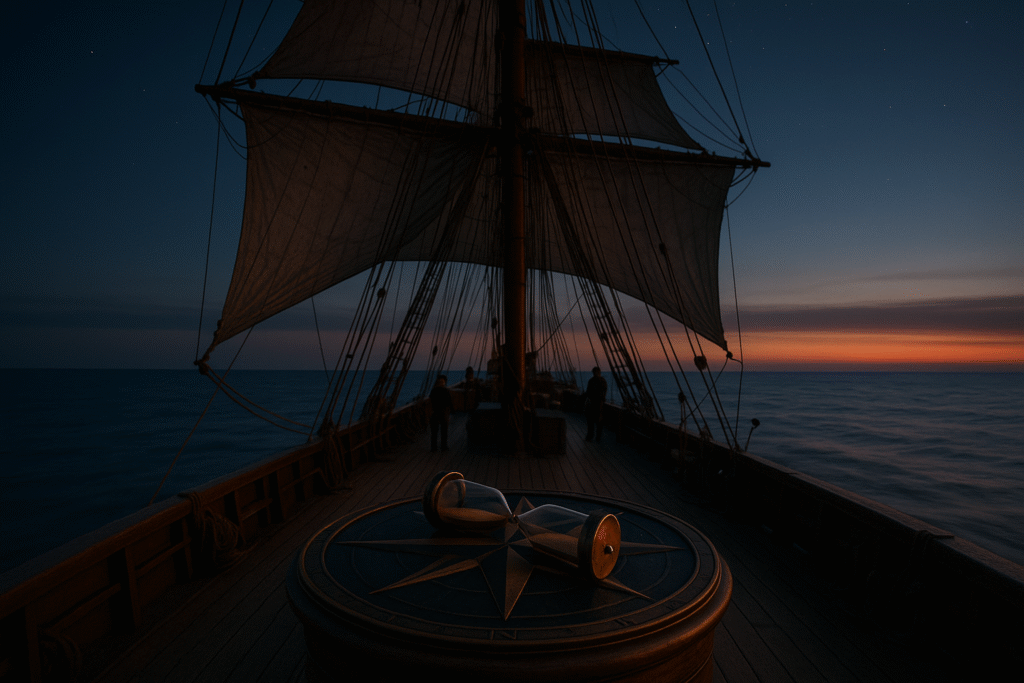

Dusk packed itself into layers: indigo first, then a dull copper seam where the sun had gone, then the thin whiteness of early stars. The water ahead looked oddly still—still like a held breath. Finn set the hourglass flat on the Prime, the mercury vane refusing to tip to either bulb.

“Stand easy, hands,” Mireya called. “Not idle—easy.”

Silas eased the hat on his brow in a way that meant he’d already chosen three different plans and was waiting for one to volunteer.

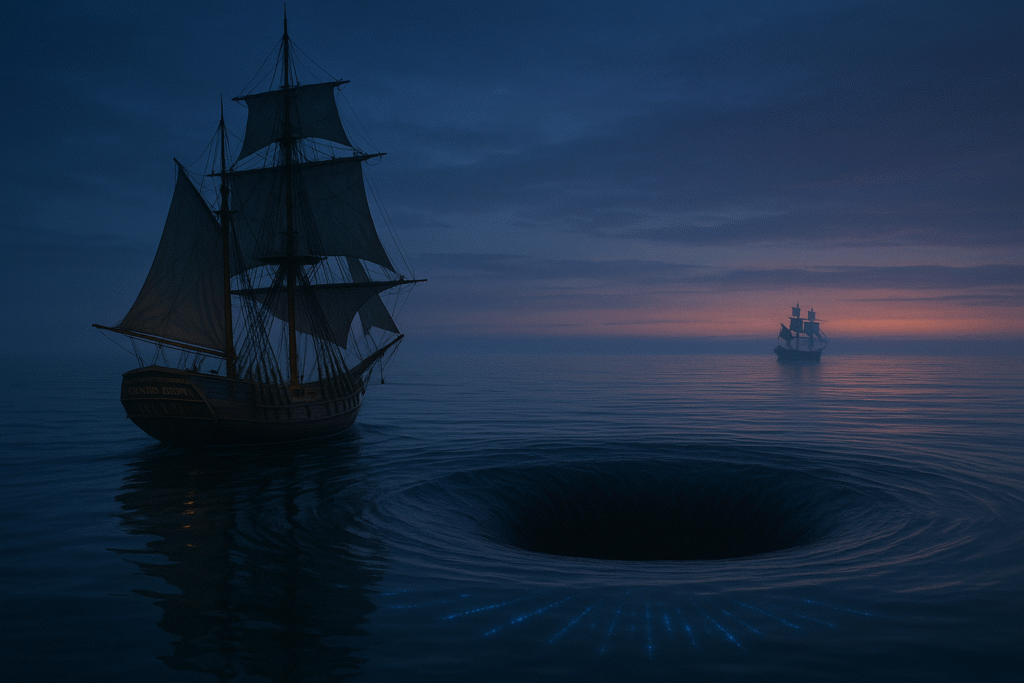

They met the Gyre at the rim: a slow collar of water turning without chop. Lanternfish sketched faint spokes deep below, as if the sea kept a clock for itself. Hayes laid the wheel a degree to starboard. The brig acknowledged, settled, and the wake untwisted behind them like a ribbon being unbraided.

“It’s a polite trap,” Briggs said. “The kind that writes to your mother after.”

“Then we’ll be better mannered,” Mireya answered.

Finn raised the Oculus. The lens returned a black iris at the center—no glare, only an absence that organized everything around it. Along the rim hung glyphs in the water: not letters, but lean angles like marks a navigator leaves on a chart when he is very sure and very tired.

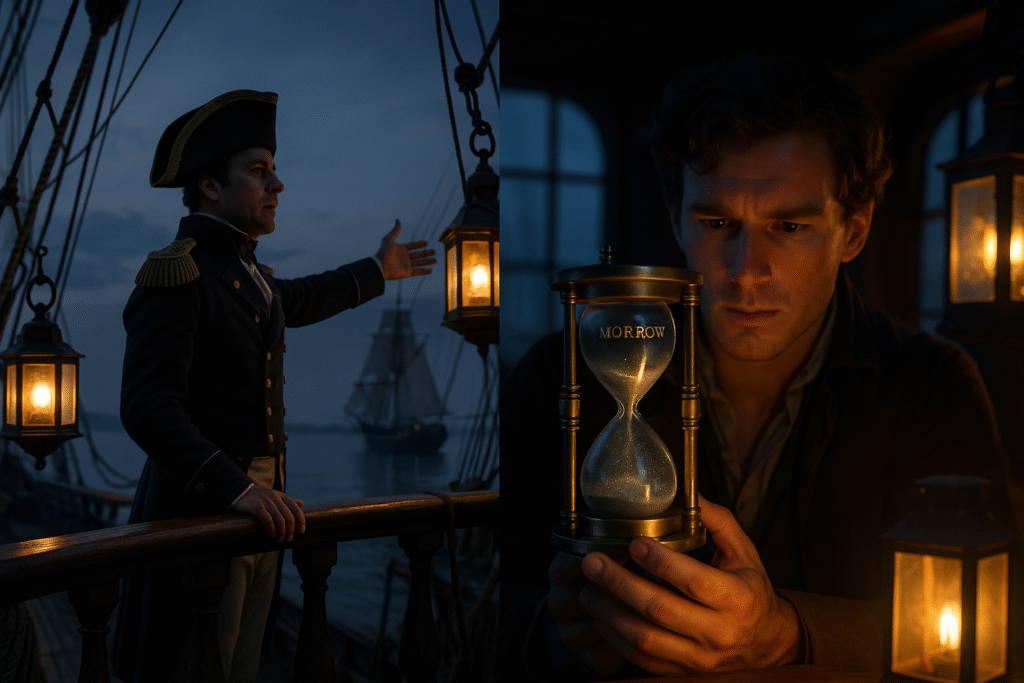

Valdés’s hail crossed the stillness as if walking. “Blackthorne! The Gyre keeps debts. Pay clean.”

Silas didn’t answer. He was watching the hourglass. Without being touched, a dusting of light began to form in the MORROW bulb. Finn lifted it; the dust stopped. He lowered it flat; the dust resumed.

“It rewards commitment, not choice,” Finn said. “Pick a drift and hold.”

“We spine the outer ring,” Mireya decided. “Quarter-sails only. Hands to braces; no heroics.”

They trimmed canvas to small honesty. The brig took the ring and matched the turn. Inside the circle, the water was darker, not thicker, as if ink had agreed to be calm.

On the third lap a low hum arrived—the kind that settles in your gums. The Prime marked a hairline toward the center; the hourglass ticked a single grain into EVE and then changed its mind, the grain hanging in the neck like a decision caught between tongues.

“We can’t hold the rim forever,” Hayes said. “She wants us inboard or gone.”

“Inboard,” Silas said evenly. “But not to the pupil.”

They cut across the ring at a shallow angle, not fighting the turn so much as disagreeing with it politely. The Gyre accepted the courtesy and allowed a passage inward. The lanternfish brightened, drawing new spokes. The spokes did not meet; they hinted.

“There,” Finn said. “Between hints.” He set the hourglass on its edge and let it lean. Light collected in the lower bulb without deciding which name it liked. The Oculus showed a narrow lane across the swirl, a place where the water pretended to forget it was turning.

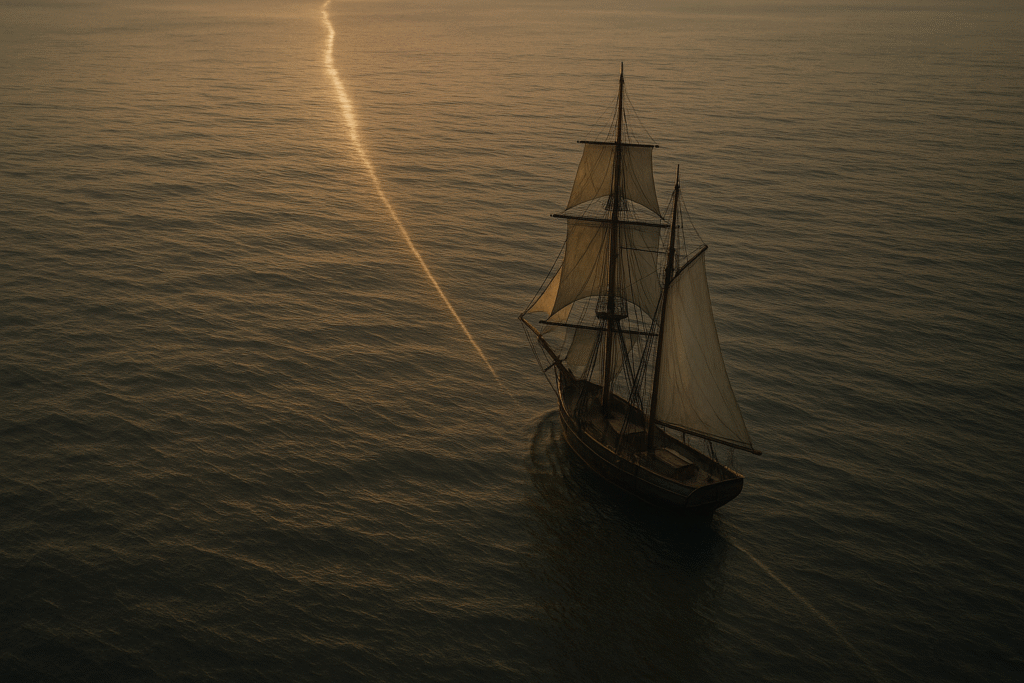

They took the lane. The rig went whisper-quiet; even Briggs stopped inventing oaths. The Crimson Horizon slid past a patch of sea that stood a finger higher than the rest, like a stitch in a sail. The Santa Lucía followed their wake exactly and then refused to follow it exactly, because pride is a kind of ballast. Her bow kissed the stitch at the wrong angle; the Ash Mirror rattled once in its case like a coin in a tin.

“She’ll learn it on the second try,” Mireya said.

“We should be gone before then,” Silas replied.

What counted for the center wasn’t a hole but a decision the sea had made and kept. It did not pull; it invited. Finn hated invitations he couldn’t read. The hourglass warmed under his palm.

“What is the toll?” Hayes asked, soft for the first time that night.

“Not time,” Finn said. “Confidence.”

He took the coin that had once been two—THEN and NOW—and set it over the hourglass so it bridged both bulbs. The coin’s hinge settled into the neck as if made for it. The hourglass answered by lighting the neck with a thread you couldn’t grab. The Prime drew a new line—no longer a heading, exactly, but a permission.

“We go through without arriving,” Finn said. “We leave a version of us going nowhere as a decoy. We take the version that has errands.”

“Spoken like a sailor and a coward,” Briggs muttered without heat.

“Spoken like a navigator,” Mireya corrected. “Do it.”

They bore up a point. The brig’s wake forked a moment—one wake pleased to continue circling forever, the other wake brief and correct. The crew felt the fork as a small guilt and a small relief at the same time.

Something below them cleared its throat. The lanternfish spokes spun once and the iris opened a breath wider, not to allow them in but to allow something else out.

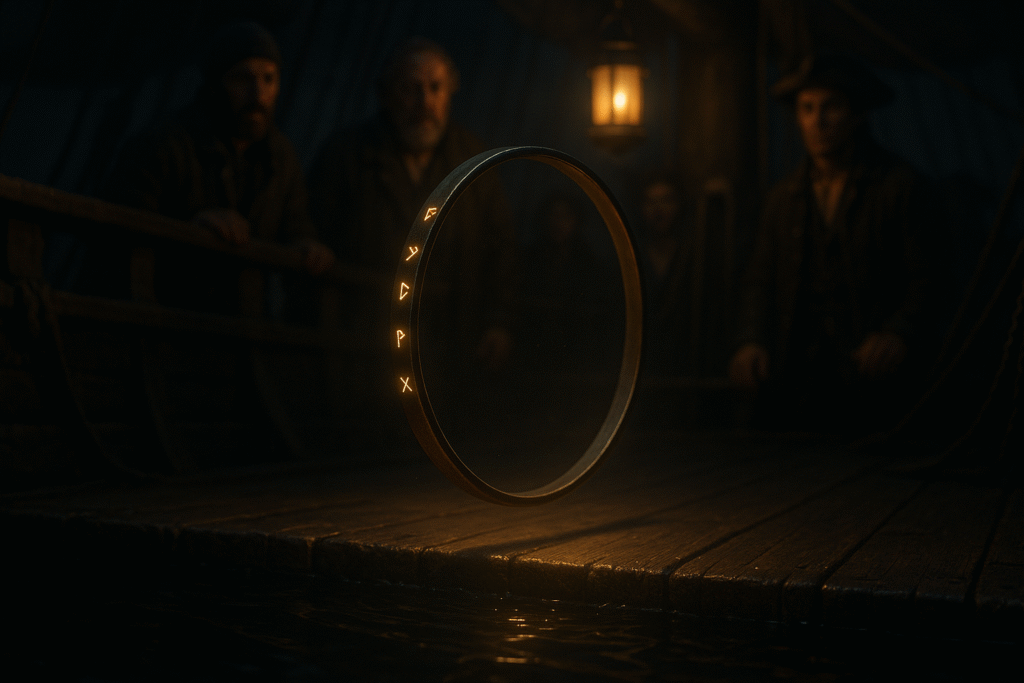

It rose like a bubble that had learned patience: a ring of metal no thicker than a knife’s back, black when you looked straight at it and pale when you looked away. Runes ticked around the rim like seconds. The ring floated for a respectful moment and then settled on the deck as if claiming a berth it had paid for.

“Name?” Briggs asked.

Finn touched it with one knuckle. The ring hummed a fifth above the ship’s hum. “Gimbal,” he said. “For keeping something true when the world is busy.”

They did not have to ask what it would keep true.

“Prime,” Mireya said, and her voice didn’t try to hide the want.

They mounted the ring under the star-compass with line and care. The mercury settled flatter than Finn had ever seen, like a lake under glass. He breathed out and wondered when he’d last been breathing in.

“Outboard,” Silas said. “Before our double starts writing letters to our mother.”

They took the lane back, faster. The Gyre did not punish them for speed; it disapproved of dithering, not of nerve. The Santa Lucía tried the stitch again and learned it on the second try, as Mireya had predicted. Valdés’s lantern tipped in brief salute that was probably not an apology.

Outside the ring, the sea remembered chop. The night remembered stars. The hourglass cooled. The coin looked pleased to have been a tool instead of an argument. The new gimbal held the Prime so steady that the slightest lie on the horizon seemed like a cracked thread waiting to be pulled.

“Course?” Hayes asked.

Finn let the compass write. It wrote a dark ribbon west-by-south toward weather that smelled like iron filings and lemons. “We’ll have rain,” he said. “And a choice that looks like a gift.”

“We’re short on gifts,” Silas said. “We’ll take one and pay later.”

From astern, Valdés’s voice arrived almost kindly. “Blackthorne! The sea teaches the same lessons to both of us. I intend to graduate first.”

“Then you’ll enjoy the exams,” Silas answered, and tipped his hat the same respectful inch.

They set canvas for the ribbon. The brig leaned into it like a dog that knows the trail. The double-wake behind them narrowed, then closed, then forgot. Somewhere under the water, the Gyre sealed its iris and went back to being a rumor the sea tells itself when it wants company.

— To be continued —