Introduction: Ahoy, Adventure! The True Story of Pirates

When we think of pirates, a colorful image comes to mind: a man with an eyepatch, a wooden leg, a colorful parrot on his shoulder, shouting a thunderous “Arrr!” and holding a yellowed treasure map where a large “X” marks the spot of a hidden chest of gold.1 Characters like Captain Jack Sparrow have cemented a romantic image of the sea rogue in our imagination—a rebel, an adventurer, and a seeker of freedom. This vision, though incredibly appealing, is largely a work of fiction, shaped by novels and Hollywood films.1

The true history of piracy is much older, more complex, and far more fascinating. The phenomenon is nearly as old as seafaring itself—mentions of sea robbers appear in ancient Greece and Rome, and even in Homer’s “Odyssey.”3 In later centuries, Vikings, whose plundering expeditions became legendary, spread terror across the seas.4

However, the period that forever defined our image of a pirate is the so-called Golden Age of Piracy. This was a short but incredibly intense time at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, when thousands of outlaw sailors created a kind of rebellious republic in the Caribbean. This was not just a wave of common crime. It was an explosive historical phenomenon, born of wars, politics, and a desperate rebellion against the brutal social order of the time. In this article, we will discover who these men (and a few women) really were, how they lived under the black flag, and what legacy—both historical and mythical—they left behind.

The Golden Age of Piracy: How the Caribbean Legend Was Born (c. 1650-1730)

Historians debate the exact timeline of the Golden Age of Piracy. Some define it broadly as the years 1650-1730, dividing it into several phases, including the buccaneer period.6 However, the heart of the legend, the most classic and intense period of pirate activity, was just one decade, from 1715 to 1725.8 It was then that a real storm broke out in the Caribbean, forever shaping the myth of the pirate.

The Perfect Storm: Causes of the Pirate Epidemic

The sudden boom in piracy was no accident. It was the result of a convergence of several key historical factors that created the perfect conditions for maritime robbery. The most important of these was the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, sealed by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.9 Overnight, powerful naval fleets, especially the British Royal Navy, were no longer needed on such a large scale. Thousands of battle-hardened, experienced sailors and privateers (legal, state-sanctioned pirates) were discharged from service and left to fend for themselves in colonial ports, without work or prospects.10

These men were victims of a system that first used them to build an empire and then threw them out on the street. The conditions of service in the navy or on merchant ships were inhumane: forced recruitment (impressment), cruel discipline based on flogging, terrible food, starvation wages, and a high mortality rate.11 In this situation, piracy appeared not only as a chance for wealth but, above all, as an act of rebellion and an escape to freedom. It was a violent response to the oppression of the Crown and ruthless merchant ship captains.11

The Caribbean at that time was an ideal place for action. Merchant ships, especially Spanish galleons carrying unimaginable riches from the New World to Europe—gold, silver, spices, and other valuable goods—constantly sailed through the region.3 Weak and often corrupt colonial authorities were unable to effectively control the vast sea routes, making them a paradise for treasure hunters.8

Pirate Republics: Lawless Havens

Pirates needed safe bases where they could repair their ships, recruit crew, sell stolen goods, and simply enjoy life. Such places emerged in poorly controlled corners of the Caribbean, creating “pirate republics.”14

- Nassau on New Providence Island (Bahamas): This place became the unofficial capital of piracy. For several years, it was a true state within a state, ruled by the pirates themselves, where thousands of sea robbers found refuge.6

- Port Royal, Jamaica: Earlier, in the second half of the 17th century, it earned the title of “the wickedest city on Earth.” It was the main base for English buccaneers until a catastrophic earthquake in 1692 swept most of the city into the sea.6

- Tortuga (Haiti): An even earlier haven, mainly for French buccaneers who hunted Spanish ships.10

The end of this unchecked activity came when the empires decided to finally deal with the pirate plague. The turning point was the arrival of a new governor, Woodes Rogers, in the Bahamas in 1718. He brought with him a fleet of warships and a royal pardon for those who would abandon their trade. The pirates faced a choice: accept the pardon, flee, or fight to the death. Many chose the pardon, while others were captured and executed. The death in battle of one of the last great pirates, Bartholomew Roberts, in 1722, and the trial of his crew, symbolically closed the Golden Age of Piracy.8

Hall of Fame (and Infamy): The Most Famous Pirates Who Terrorized the Seas

The Golden Age of Piracy produced a whole galaxy of legendary captains whose names still evoke fear and fascination today. Their stories are a mix of brutality, bravado, and an extraordinary talent for building their own myth.

Edward “Blackbeard” Teach (d. 1718)

Blackbeard is the archetype of the demon pirate. His greatest weapon was not firepower, but psychological terror. Edward Teach perfectly understood the power of image and consciously created his terrifying legend. His nickname came from his thick, black beard, into which he would weave hemp fuses and light them before battle. Boarding an enemy ship shrouded in a cloud of smoke, with his eyes burning in the dark, he looked like a messenger from hell.16 He commanded a powerful, 40-gun ship which he named

Queen Anne’s Revenge.17 His most famous feat was the audacious blockade of the port of Charleston, South Carolina, which he forced to pay a ransom of… a chest of medicine.19 He died in 1718 in a bloody battle with the crew of Lieutenant Robert Maynard. His severed head was hung from the bowsprit of Maynard’s ship as a warning to others.14

“Calico Jack” Rackham, Anne Bonny, and Mary Read (d. 1720)

John “Calico Jack” Rackham is remembered in history not so much for his piratical successes as for his extravagant style (his nickname came from his fondness for colorful calico clothes) and his unusual crew, which included the two most famous female pirates in history.20

Anne Bonny and Mary Read were women who broke all the conventions of their time. Both had to pretend to be men to enter the male world of sailing. However, they quickly proved that in a fight with sabers and pistols, they surpassed many a crew member.20 A remarkable bond formed between them on Rackham’s ship—some historians speak of a deep friendship, others of a romance.20 Their end came in October 1720, when their ship was attacked by pirate hunters. While Rackham and most of the male crew were completely drunk and surrendered without a fight, Anne and Mary fought to the very end, trying to organize a defense.20 The entire crew was sentenced to death, but both women avoided the gallows by declaring in court that they were pregnant (“pleading the belly”).22 Legend has it that the last words Anne Bonny said to Rackham as he was being led to the gallows were: “If you had fought like a man, you need not have been hang’d like a dog.”23

Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts (d. 1722)

Although less known in pop culture than Blackbeard, Bartholomew Roberts was undoubtedly the most successful pirate of the Golden Age. In a career spanning just a few years, he captured over 400 ships. Contrary to the image of a ragged scoundrel, “Black Bart” was an elegant man—famous for wearing scarlet silks, a feathered hat, and a diamond necklace.25 His death in battle off the coast of Africa in 1722 and the subsequent trial and mass execution of his crew are widely regarded as the symbolic end of the Golden Age of Piracy.8

Captain William Kidd (d. 1701)

The story of Captain Kidd is a tale of how a man becomes a myth. Kidd was not a typical Caribbean pirate. He started as a respected privateer, hired by English lords to hunt pirates in the Indian Ocean.27 However, the line between privateering and piracy was thin. Accused of treason and piracy, he was captured, tried in London, and hanged in 1701.14 Just before his death, he claimed to have hidden a huge treasure somewhere. Although this was likely an attempt to buy his life, the rumor took on a life of its own. The story of Captain Kidd’s supposedly buried treasure became the inspiration for countless tales and gave rise to one of the most enduring pirate myths—the map leading to hidden wealth.2

Life Under the Black Flag: Democracy, Code, and Brutal Reality

A pirate ship was a world unto itself, operating according to rules radically different from those on land. It was a kind of floating, democratic utopia, yet it was based on violence and doomed to a short, though intense, existence.

The Pirate Code: Constitution of the Sea Rebels

Every pirate ship was governed by its own set of laws, known as the “articles of agreement” or simply the pirate code. These were not top-down rules but a social contract that every new crew member had to accept and sign (or make their mark if illiterate).18 The code regulated all aspects of life on board: from the division of spoils, to rules of discipline (e.g., no fighting on the ship), to access to alcohol.18

Democracy at Sea: Captain and Quartermaster

The power structure on a pirate ship was revolutionary. Unlike the autocratic rule on naval and merchant ships, pirates introduced a system based on democracy and the separation of powers.

- Captain: He was elected by the crew in a vote and could be removed from his position at any time.26 His authority was absolute, but only in two situations: during battle and in pursuit of a prize.30 He was a military commander, not a tyrant.

- Quartermaster: This unique pirate position was as important, and on a daily basis even more important, than the captain’s. The quartermaster was also elected by the crew and served as their spokesman and advocate.32 He was responsible for maintaining order, settling disputes, rationing provisions, and—most importantly—supervising the fair division of loot. Outside of combat, he had the right to veto the captain’s decisions, protecting the crew’s interests.26

Pirate Insurance: Compensation for Injury

Pirate codes included what we would today call a social insurance system. The crew agreed in advance on the amount of compensation for injuries sustained in battle. It was a form of recompense for sacrifice for the community. The rates were precisely defined; for example, in one ship’s code, the loss of a right arm earned a pirate 600 pesos (or six slaves), a left arm or right leg 500 pesos, and an eye or a finger 100 pesos.33

The Grim Reality: Dirt, Hunger, and Disease

Despite these progressive rules, the daily life of a pirate was far from romanticized notions. It was a life of filth, discomfort, and constant danger.

- Food and Drink: Provisions on long voyages were monotonous and often spoiled. Hardtack biscuits became stale and infested with weevils, and salted beef hardened to the point that it was used to make buttons.16 Water in barrels quickly went bad. Therefore, the primary drink was grog—a mixture of rum, water, and lemon juice. The alcohol killed bacteria in the water, and the citrus protected against scurvy, a deadly disease caused by a lack of vitamin C.18

- Hygiene and Health: Hygiene was minimal. Pirates wore the same clothes for months until they literally fell apart.16 They used saltwater for washing, which led to skin diseases and irritation. Teeth were cleaned by chewing on wooden sticks, which did not prevent their loss.16 A pirate’s career was short and brutal—if he didn’t die in battle or on the gallows, he was often killed by disease, wounds, and the terrible living conditions.18

- Discipline: Although pirates valued freedom, breaking the code was severely punished. The most serious offenses, like theft or desertion in battle, were punished by death or marooning on a deserted island—which was often a sentence of death by agony.14

Jolly Roger: Anatomy of the Pirate Flag

No symbol is as inextricably linked with pirates as the black flag with a white skull and crossbones. However, the history of the pirate flag, known as the Jolly Roger, is more complex than it might seem.

A Tool of Psychological Terror

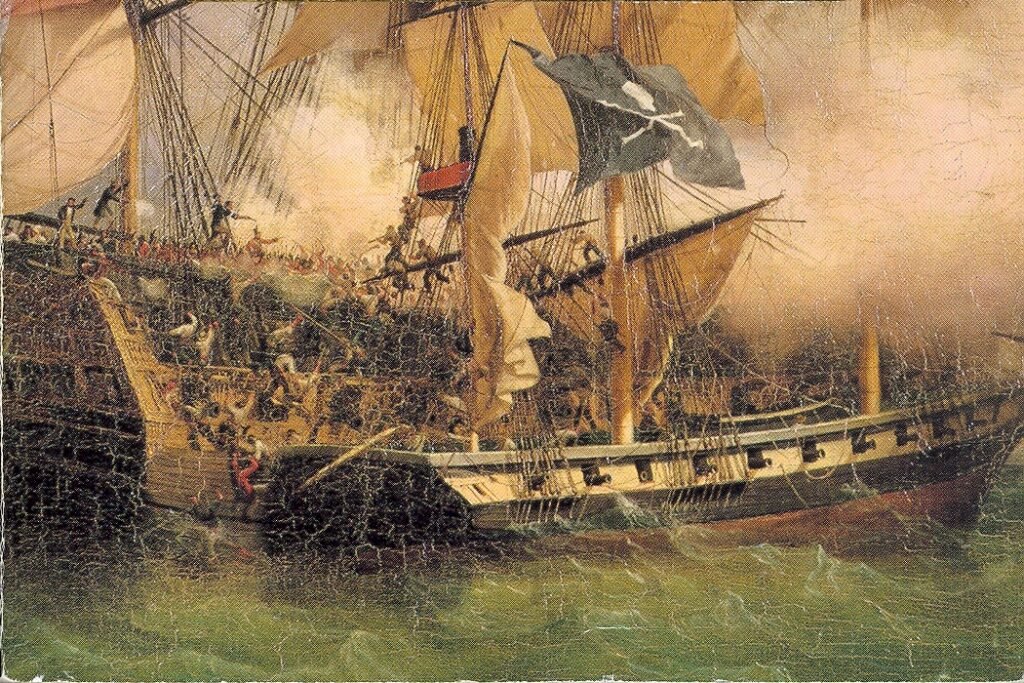

First and foremost, the Jolly Roger was not just a decoration. It was a powerful tool of psychological warfare. Its main purpose was to instill such terror in the crew of the attacked ship that they would surrender without a fight.35 Pirates preferred to avoid battle, which always carried the risk of damaging their own ship and losing men. The sight of the black flag was a clear message: “We are pirates. Surrender, and we will spare your lives. Resist, and you will die.”

For this reason, pirates rarely flew their true flag all the time. They used deception: they would approach their victim under a false flag, such as Spanish or English, lulling its crew into a false sense of security. Only at the last moment, when escape was impossible, would they hoist the Jolly Roger, amplifying the effect of shock and panic.35

Black or Red? The Color That Decided Life and Death

Contrary to popular belief, pirates used not only black flags. There was another, much more sinister variant.

- The Black Flag: This meant that if the ship surrendered without resistance, the crew would be spared (given quarter). The loot would be taken, but the people would survive.25

- The Red Flag: Sometimes called Jolie Rouge (“pretty red” in French, which is one possible origin of the name “Jolly Roger”), it was a signal that the pirates would show no mercy. It meant a fight to the death, with no prisoners taken. Everyone on board the attacked ship was to be killed.25

A Gallery of Death: The Personal Coats of Arms of Pirate Captains

The term “Jolly Roger” referred to any pirate flag, and these varied significantly. Many captains created their own unique designs, which were meant to reflect their reputation and serve as a personal “trademark.”

| Captain | Flag Design | Symbolism |

| Edward “Blackbeard” Teach | A skeleton holding an hourglass in one hand and a spear piercing a bleeding heart in the other.41 | “Your time is running out” (hourglass), “surrender or face a painful death” (spear and heart). |

| “Calico Jack” Rackham | A skull above two crossed cutlasses.25 | The classic symbol of death combined with the tools of pirate combat, symbolizing readiness for battle. |

| Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts | A pirate figure standing on two skulls, under which are the letters ABH and AMH.25 | “A Barbadian’s Head” and “A Martiniquan’s Head”—a personal threat to the governors of Barbados and Martinique who had sent ships after him. |

| Edward Low | A red skeleton on a black background.25 | A symbol of brutality and death, reflecting Low’s reputation as one of the cruelest pirates. |

Fact or Fiction? Debunking the Biggest Pirate Myths

Pop culture has created many colorful but untrue myths about pirates. It’s time to separate fact from fiction.

Myth: Pirates forced captives to walk the plank.

Reality: This is one of the most famous, but almost entirely fabricated, images. It was popularized by the novel “Treasure Island.”44 Although isolated incidents may have occurred, especially during mutinies, it was not a standard practice for pirates of the Golden Age.45 Pirates were practical and brutal people—if they wanted to kill someone, they simply killed them or threw them overboard, without unnecessary theatrics.14

Myth: Pirates buried treasure and created maps with an “X.”

Reality: The vast majority of pirates spent their loot as quickly as they got it—mostly on alcohol, gambling, and pleasures in port taverns.18 The idea of burying treasure comes almost entirely from the story of Captain William Kidd, who allegedly hid part of his fortune before his arrest.2 This myth was immortalized in “Treasure Island.” In reality, pirates’ loot was rarely gold itself. More often, they captured valuable goods like spices, silk, weapons, and even mundane items like food and medicine, which were more valuable at sea than precious metals.2

Myth: Every pirate had a parrot on his shoulder.

Reality: We also owe this image to “Treasure Island” and the character of Long John Silver with his parrot, Captain Flint.48 While sailing in exotic waters, pirates did encounter parrots and other exotic animals. They were a valuable commodity in Europe, so they were sometimes caught, but they were treated more as cargo for sale than as pets.48 A much more practical and common animal on a ship was a cat, which killed rats that destroyed supplies and ropes.50

Myth: The eyepatch was used to hide an empty eye socket.

Reality: Of course, in the brutal world of pirates, losing an eye in battle was not uncommon. However, there is another, more fascinating and scientifically plausible theory. The eyepatch could have been a tactical tool used to preserve night vision.16 The human eye needs up to 25 minutes to fully adapt to darkness after moving from bright sunlight.16 A pirate fighting on a sunlit deck and then going below deck, where it was dark, would be practically blind for a moment. By wearing a patch over one eye, he kept it constantly adapted to the dark. When going below deck, he only needed to switch the patch to the other eye to immediately regain vision in the dark.34 Although there is no direct historical evidence for this, the theory is considered highly probable.54

Myth: Pirates said “Arrr!”

Reality: This is 100% a Hollywood invention. The stereotypical “pirate accent” was created and popularized by actor Robert Newton, who played Long John Silver in the 1950 Disney adaptation of “Treasure Island.” Newton, who was from the West Country of England, used an exaggerated version of the local dialect, which is characterized by a hard, rolled “r.” His performance was so memorable that it forever defined how pirates “should” speak in movies.47 Real pirates came from all over the world and spoke with a wide variety of accents.58

Conclusion: 21st-Century Pirates – The Spirit of the Past on Modern Waters

The Golden Age of Piracy ended almost 300 years ago, crushed by the power of maritime empires. However, its legend, fueled by literature and cinema, lives on and is doing very well. The romantic myth of the rebels under the black flag still captures the imagination, but it is worth remembering that piracy as a phenomenon has never disappeared from the seas.3

Modern piracy is a serious and brutal problem that threatens international trade and maritime security.59 Instead of wooden sailing ships, today’s pirates use fast motorboats, and instead of cutlasses and muskets, they use automatic rifles and GPS navigation.3 Their main hunting grounds are no longer the Caribbean, but the waters off the coast of Somalia in the Gulf of Aden and the Gulf of Guinea off the coast of West Africa.60 The goal of attacks is rarely the direct robbery of cargo anymore. Much more often, pirates hijack ships and crews for ransom, turning maritime robbery into a profitable business.3Interestingly, the roots of modern piracy are strikingly similar to those of centuries ago. It is still a phenomenon born of poverty, unemployment, lack of prospects, and political instability on land.62 Although the wooden ships and skull-and-crossbones flags have disappeared, the desperation that drives people to attack ships at sea remains unchanged. The romantic legend lives on in pop culture, but the harsh reality of piracy continues to be a real threat on the world’s oceans.